A quick photographic excursion to explore and capture natural & anthropogenic wonders, through the mind’s eye, the SLR lens and to etch them in the warp & weft of memory is now an intermittent detour from my hectic life. It is a ‘health break’, to use modern phraseology that describes necessary physical and mental activities, intended to maintain balance & composure in the face of taxing official work.

An arduous roundabout journey via Delhi and Varanasi, took us to the quiet backwater of Khajuraho in Central India, and transported us straight into the scene of a prolific medieval architectural effervescence. Here is lost, thanks to modern geography & geopolitics, the reality of a medieval polity & society. Modern knowledge baffles us why, in the middle of ‘nowhere’, a huge capital should spring up as a focal point of political power, or as an important signpost on a trade artery? Why should modern day Chattarpur, that (even?) today is ill-connected, be the heart of an medieval empire? Or why should the dusty, pot-holed town of Dhar be the core of a fecund imagination of a pre-Islamic India? Knowledge illuminates, even as it excludes; and so is it with the modern worldview that blinds us to the past- even as past is staring at us in the eye.

Khajuraho, geographically not too far from Varanasi & the heartland of Harshavardhana’s empire-Kanauj, was a seat of his important feudatories, the Chandelas. This land was known as Jejakabhukti and till the ascendance of the Chandelas found little mention in the history of India, except a passing reference as ‘atakiva rajas’ during the janapad period of settlement indicating indigenous political systems in the thick forests. Found in the heart of a latter-day Gond Kingdom, successful sanskritization identify them as Rajput-Gond stock. Fortuitously, their contact & adherence to the Hindu tradition and religion made them the harbingers and patrons of effervescent Hindu socio-religious sculpture & art.

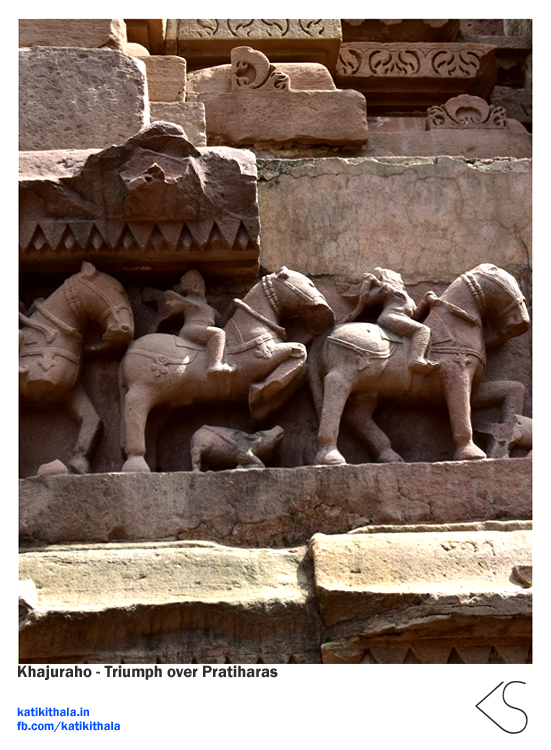

Religious & secular sculpture of this period simultaneously instructed the onlooker of social mores, elevated the devout, celebrated the divine & recorded for posterity; all of this. Emerging from the shadow of their suzerains, the Pratiharas, the Chandela emblem- nyala (a mythical tiger-lion) slowly replaced the wild boar–varaha, and successive Chandela Chieftains commemorated each exploit and success. The first notable Chief was Harsha who successfully repulsed the Rashtrakuta forays and reinstated his Sovereign Mahipala on the Throne of Kannauj and built the Matangeshwara Temple, which is amongst the few of the Chandela temples that are still used for worship. His son, Yashovarman alias Lakshavarman built the Lakshmana temple to record his successful military exploits against the the Rashtrakutas of the west and the Palas of the east. The Chandela tradition of naming a temple after the builder-king and not the diety began with him. The Lakshmana temple represents a high point in Central Indian temple architecture both in terms of its intricacy, details as well as architectural elements; it also represents a crossover in the various traditions of the Nagara Style: the Orissa, the Gujarat-Rajasthan & the Central Khajuraho. A curious coincidence between Khmer-Hindu activity in the same period & the Chandela can also be discerned. Like the Khmers who also built exuberantly during the same period, albeit a few thousand miles away, the Chandela rulers built temples to commemorate their rule; however, unlike the Khmers, they didn’t deify themselves but instead named their temple edifices after themselves. The similarities do not end there: a visit to the western enclosure of the Khajuraho temples complex is quite like a trip to the APSARA complex of Siem Reap.

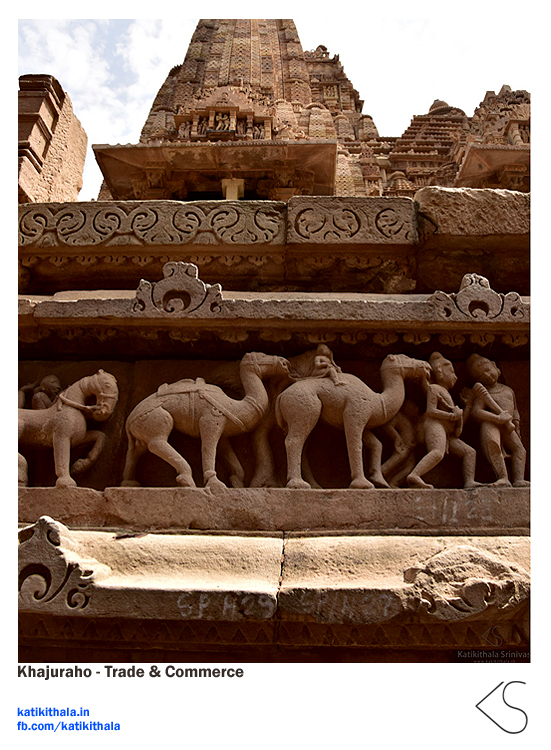

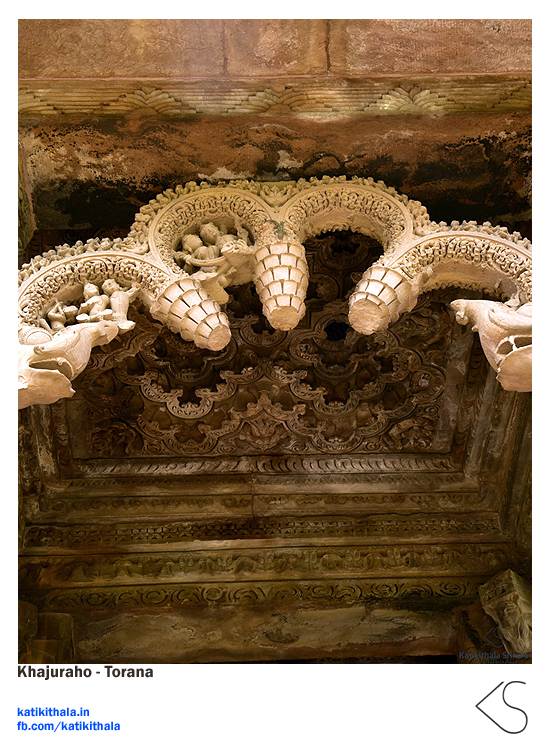

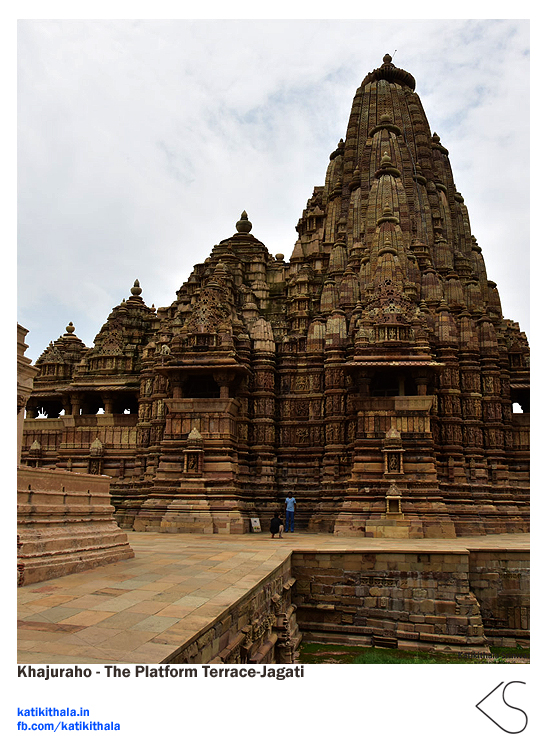

The Chandelas were a tolerant dynasty and encouraged both Hindu & Jaina temples, and glimpses of this catholicism are evident in the abundant Jain temple architecture in the eastern enclosure. Stylistically, the Khajuraho temples follow the Nagara tradition with a slight embellishment-the panchajanya (five-shrine) model, where the main sanctum is surrounded on all the cardinal points by subordinate structures for other deities. Adapting to the local soil conditions, all temples are raised on a platform, called the jagati. The jagati itself is embellished on the frinze with friezes depicting various secular, religious, social, moral, military & mithuna themes. A flight of stairs to the top of the platform reach the main structure and typically a lofty basement storey called the adhishthana rises from the terrace in a rolling series of mouldings to the next & final level of access. A flight of stairs allows the devout to surmount the adhishthana and reach the first of the formal series of chambers, the ardha mandapa. This level can be termed as the sacred-devout level, which horizontally evolves through various chambers intended to accommodate myriad secular & sacred actions, the final act of piety being in the Garba Griha. The entrance to the ardha mandapa is distinctive being defined by elaborate sculpted brackets-the toranas.

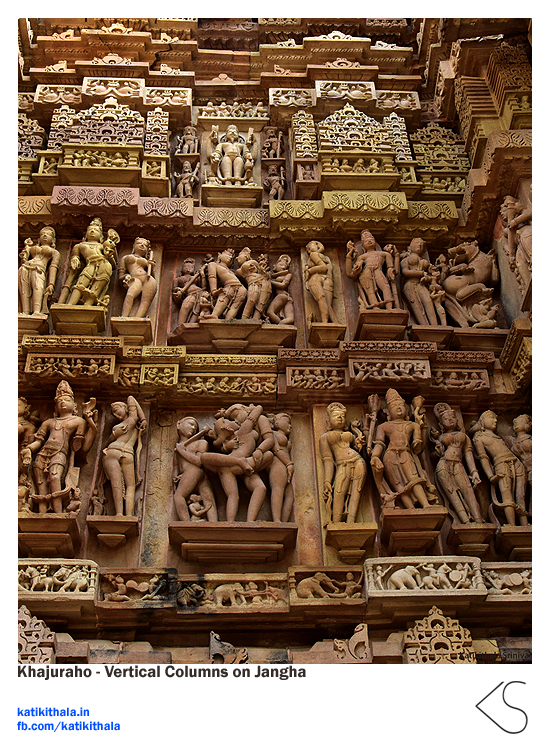

The main wall of the structure called the jangha, rises from the platform-terrace (jagati), supports the many fenestrations of each chamber and loftily reaches the skies through the shikhara structures. The jangha is richly festooned all around with a profusion of sculpture depicting various themes. It is easy to get lost in the myriad detail of the rich sculpture and fail to discern a pattern. However, it is there to be seen. On the jangha the base usually has a procession just as in most other temple architecture-elephant, lion, lotus friezes, support the vertical elements. The vertical elements on the jangha consist of central column features and the corner features-the former a definite pattern with formal deities providing the foci for a grouping of sculpture that rises in a column.

The Sculpture on Kajhuraho are of five (5) types:

- Formal deities: The Presiding dieties, such as Vishnu, Siva; which are executed true to sastra & are whole-rounded.

- Avarna devatas, parivara & parsva : They’re the attendant minor divinities, family etc which are usually found in niches or against the walls in medium of high relief

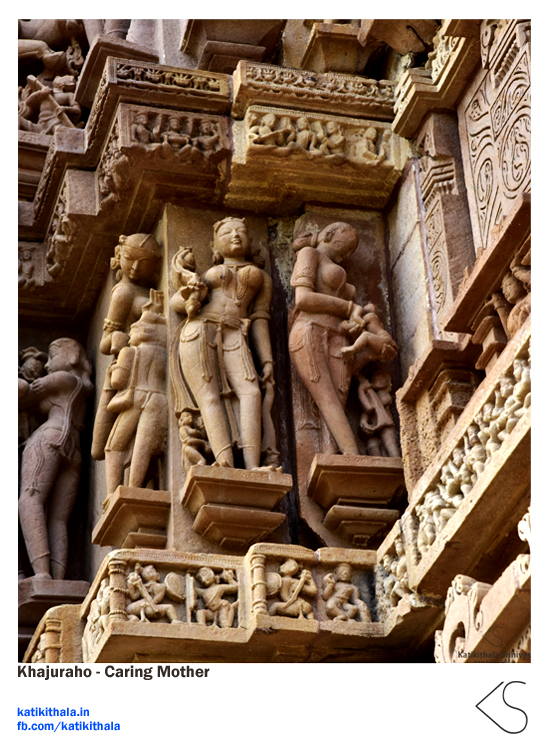

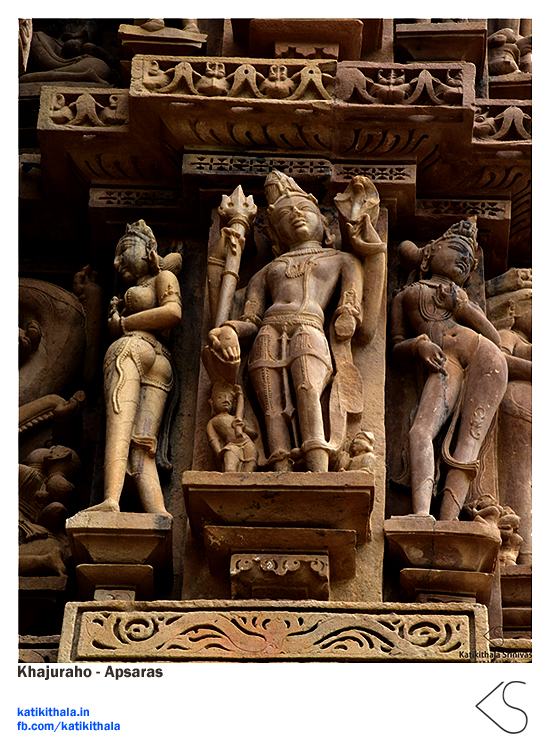

- Apsaras & Sura-Sundaris

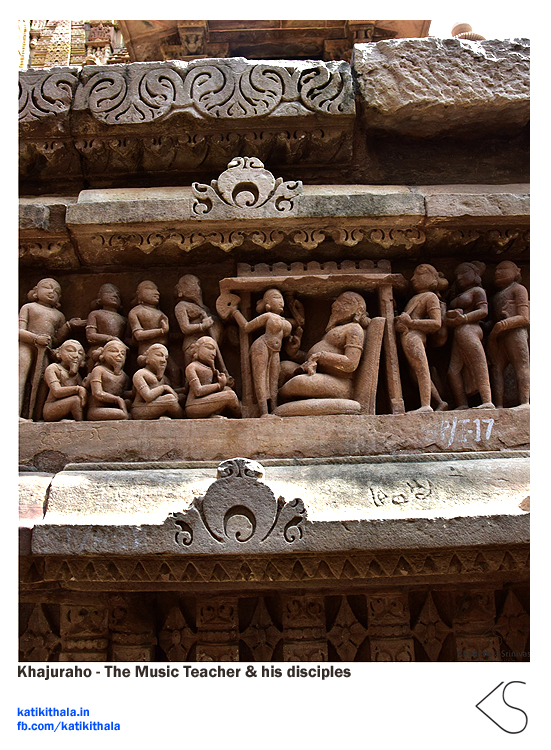

- Secular Sculpture

- Animals, including mythological vyala or sardula, which is represented as a rampant horned lion

Formal deities such as Vishnu, Siva are fully sculpted in a three dimensional form and are seen in complete adornment & are identifiable by their insignia such as the trisula for Siva or the chakra in the case of Vishnu. These cult figures are also identified by the other sculpture that comprises their cortege, which fulfill the Hindu tradition of complementing invocation of a Great one with the accompanying court.

Avarna devatas, parivara & parsva sculptures depict the family, attendant & accompanying divinities. They occur in specially defined niches as well as in relief, however, in the former these divinities are defined in greater detail and assume iconographic quality. When found in relief these include dikpalas, the masters of the eight directions and are less formal.

Apsaras & Sura-Sundaris are profuse secular sculpture seen depicting a range of human emotion, action. The sura-sundaris are extraordinarily graceful and attired in the finest robes, jewelry. They are imbued with poetic grace and found in a wide variety of human postures-bending to rub their back, pick a thorn from the foot, disrobing and so on; in these is found the lyrical quality of Khajuraho sculptures. Apsaras are usually found on a dancing posture; and attendants are seen assisting the higher divinities by offering lotus-lower, carrying mirror, ornaments etc.

Secular sculpture portrays the social times and often instructs. Many panels of instructions in music, of teachers & disciples and so on also serve to commemorate the master craftsmen. The erotic sculpture of Khajuraho is well known, and according to some views, owes its fame/notoriety gained ground during the flower power generation which saw adherents of the hippie movement seek self-actualization.

Finally Animals, including mythological vyala or sardula, which is represented as a rampant horned lion are profuse. They follow a sculptural tradition that is extant all over India-the Vyala in South Indian temple architecture is known as yali, and serve as brackets, as buttresses and so on.

The Khajuraho temples follow the main traditions of Central Indian architecture. The Nagara tradition of Central Indian temple architecture beginning with Orissa, evolves into a more profuse form in the Khajuraho & Budelkhand series and finally culminates with the Gujarat-Rajasthan. At Khajuraho, the link in the series can be found in the Lakshmana temple, where the Kumbha motif used in the Shikhara, is an element borrowed from the Orissa school. However two important differences can be perceived; while in the Orissa school there is no raised platform-terrace (jagati) owing to its firm foundational soil, in the Khajuraho school not only is there a terrace but also present are enhancements in the four cardinal points.

The temples themselves are of two types-ones that allow circum-ambulation called sandhara and those that don’t allow pradikshina, named nirandhara. The Temple is a procession of action, emotion and a hierarchy of sanctity. Beginning with the Makara Torana, moving onto to the Ardha Mandapa that leads on to the Mandapa that serves as the main activity area, progresses to the transition-the Antaraal and finally the Garbha Griha. It is the journey from the mundane to the sublime, and from the temporal to the spiritual. It is upliftment of the human body, mind & soul exhorted to rise towards the divine along the towering shikaras.

Reference:

- Krishna Deva, Temples of Khajuraho

- Khajuraho-World Heritage Series, Archeological Survey of India